At a friend’s birthday party in 7th or 8th grade, we watched The Exorcist. For fun. “Ha, ha, let’s watch a horror movie with terrible special effects.” I had never heard of it. Someone put it on, turned out the lights, and almost immediately the future adult in my mind was thinking, “We should not be watching this. What kind of parents would allow a group of 12-year-olds to watch this? We should not be watching this.”

At a friend’s birthday party in 7th or 8th grade, we watched The Exorcist. For fun. “Ha, ha, let’s watch a horror movie with terrible special effects.” I had never heard of it. Someone put it on, turned out the lights, and almost immediately the future adult in my mind was thinking, “We should not be watching this. What kind of parents would allow a group of 12-year-olds to watch this? We should not be watching this.”I spent the next two hours with my back against their living room wall, watching intermittently through my clenched hands, sometimes plugging my ears, every good humor in me petrified. I didn’t speak as we waited to be picked up after the party ended. Everyone else was joking, laughing, pushing cake in each other’s faces. When I got home and saw my mother, I burst into tears. I was so terrified that I didn’t feel shame in doing this. I was hysterical. I did not sleep that night. Yes, we laugh about this now, but that terror was very real at the time. No movie has done that to me before or since.

At that point I had been raised as a habitual Catholic and had not bothered to ponder religion or spirituality. Church was something rote but comforting done once a week, like it or not. Religion in a Catholic grade school fostered complacency or, at least, spiritual laziness. Pray to God, give thanks, say three Hail Marys after confession, blah blah.

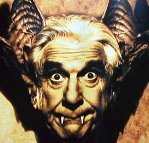

Into the blank slate of my mind came The Exorcist, which did the thinking for me. It was a rough initiation into the realm of spiritual questioning. “The devil is real, and he works his evil on undeserving people,” the movie said to the 12-year-old me. “There is no reason to it. It happens.”

In high school, I discovered, to my utter horror, that my family actually owned William Peter Blatty's novel. I found it while rummaging through the attic of our home in Buffalo. That purple paperback cover. That white, soulless face plastered across the front. I was upset by this discovery and decided the only logical thing to do was to read the damn thing and exorcise The Exorcist from myself.

I read it in one sitting, alone in the house on some dark weekend. To leave it unfinished would mean the story was still happening in the ether. It needed to be concluded. Irony: I loved the book, especially the end. My bleak grade-school assessment of the movie was tempered by an evolved understanding of and appreciation for faith and doubt. I was very moved in the final pages when Fr. Karras squeezes Fr. Dyer's hand to affirm his belief in God during last rites at the bottom of the steps -- even though he has just seen irrefutable proof of evil.

Despite this, I had no desire to endure the movie again. Until now. For reasons unknown to me, I felt compelled to watch it Sunday night, alone, in the dark, not two miles from Georgetown, where it takes place. From its opening scenes, it conjured in me a queasy dread. But now, as a more nuanced 23-year-old, I was able to appreciate why and how it conjured the dread. It is a singular movie-watching experience; it's a full-on psychological attack on the viewer that is tactical, not sensational. The first hour of the movie is all atmosphere. Noises. Insinuations. Half-hearted diagnoses. But it all has a locomotive power that builds and builds.

Here are the notes I scribbled during it:

1:30 - Friedkin's introduction. He talks about how The Exorcist makes you question your sanity. Great. I always worried that watching the movie again would unhinge me in some way. You see how affecting this movie was on a 7th grader?

2:01 - Just seeing those red block letters (THE EXORCIST) freezes my spinal fluid.

8:00 - Fr. Merrin's clock stops in Iraq. I still remember the image vividly from the first viewing. It is so simple. Conveys the perfect sense of metaphysical dread.

11:50 - And I remember those fighting dogs, too, and Max von Sydow staring down that statue. I am queasy. We are reminded daily by our government that there is evil in our world, and that we are fighting it. And either in the real life or The Exorcist, they say it comes from Iraq. Go figure.

13:15 - This is what I found so scary the first time -- those noises from the attic. A house naturally creaks and groans as the temperature drops at night, but after watching this it seems like the most unnatural thing. It plants the seed of doubt in your mind.

34:06 - The defiled statue of Mary. Another image that was seared into my brain. The perversion! But it's nothing compared to the perversion to come.

47:09 - The battery of clinical tests perpetrated on Regan is almost as terrifying as the demonic possession. Spinal taps. MRIs. The poking and prodding. Clicking machines. The scientific rationale. The insidiousness of a white hospital room. Of a needle administered.

56:00 - I can't imagine seeing this movie in theaters, where you can't control the volume of the sound. I am watching it with one finger on the volume button, because I find the audio aspect the most terrifying. While most horror movies make me close my eyes, this one makes me plug my ears.

1:05:22 - Conflict + guilt = a body invaded by a spirit?

1:07:15 - A belief in the power of exorcism can combat the belief that the body is possessed by a spirit. Is there no reality to life? Only the perception of reality?

1:22:00 - The scariest part is this thing that says it's the devil not only "knows" Karras' mother is dead, but also that she's in hell. It could be a manifestation of guilt or remorse. How could Karras not be more phased by this? This is one of the failures of the movie: that it doesn't show Karras profoundly scared and flabbergasted from his first, wretched encounter with the girl. He seems to be taking it in stride.

1:26:30 - I am fascinated by faith and doubt, and the scenes of Karras "celebrating" Mass have tremendous weight as the story progresses. Especially shots of the transubstantiation, which is really its own form of imposed possession, right?

1:30:00 - Is the possession caused by a father complex? Burstyn can certainly relate from her real-life experience. Her autobiography refers to a "father-shaped hole" in her heart. In The Exorcist, that hole is filled by a demon.

1:34:00 - Even after all this -- the vomiting, the speaking in tongues, the thrashing, the "telepathy," the word-shaped scarring on her stomach -- Karras still has doubts about whether the child is possessed? This is where the movie doesn't make sense.

1:37:00 - I love how Max von Sydow is the hero, and how even the devil knows him, and how he doesn't flinch when the devil calls him by name, as if he's done personal battle with Satan before. Which he has -- von Sydow spent much of his career previous to this role as Ingmar Bergman's go-to metaphysical protagonist.

1:38:00 - "The attack is psychological." Indeed.

1:39:00 - There is something about priests going up against evil. I have great respect for most clergy, especially Jesuits (but not the Catholic Curch as an institution). It is adrenalizing to see them "suit up" and march unblinking toward the great battlefield of good and evil.

1:51:00 - It's really two movies in one: Burstyn's and Jason Miller's. She's barely in the second half; he's barely in the first.

1:54:00 - Never underestimate the scare power of a well-timed phone ring.

1:55:00 - Lots of people think this movie is a laugh riot. It isn't. For me. But...it is kind of comical when Karras slugs the girl at the climax. It's comforting to know that the devil in this movie is punchable. I almost want a "POW!" or "ZOCK!" to flash on the screen at this moment.

2:00:00 - The end. As always, things loom larger in the memory. I'm going to be able to sleep tonight. There is a twitch of disappointment in this -- I believe in the power of movies, and part of me would've been delighted if this movie sent me straight back into my own personal loony boon. Alas, it didn't. Does this mean I'm an adult? Now that's scary.

.jpg)