A couple months ago, the Internet Movie Database started tagging movies with "plot keywords," which for me have been a source of great amusement. So let's have some fun. Below are a list of nine movies. Below that list are their featured plot keywords as they appeared on Wednesday (they tend to fluctuate). Match the movies with the keywords. For the answers, look at the first comment. Careful: It's a little tricky.

Brokeback Mountain. Gigli. My Best Friend's Wedding. Riding the Bus with My Sister. Saw. Singin' in the Rain. The Sixth Sense. Sunset Blvd. When Harry Met Sally...

1. Wedding / Distress / Bar Scene / Bear / Blood on Shirt

2. Rain / Pie In The Face / Friendship Between Men / Pun / Biplane

3. Cuckold / Impersonation / Refuge / Camera / Self Hatred

4. Diorama / Repentance / Disturbing / Surprise Ending / Wife

5. Understanding / Enigmatic / Psychology / Trauma / Affection

6. Romance / Quest / Heir / Rival / Revenge

7. Restaurant / Writer / Romantic Comedy / Kiss / Telephone Call

8. Cult Favorite / Black Belt / Photography / Tae Kwon Do

9. Critically Bashed / Mentally Disabled / Yoga / Character Name In Title / Product Placement

You can also search the database by keyword. For example, "vomit" calls up 261 movies, including Stand By Me, Apollo 13, The Rock, Space Cowboys and Seabiscuit. Useful! Have you come across any crazy plot keyword combinations? If so, share in the comments.

Friday, March 30, 2007

Thursday, March 29, 2007

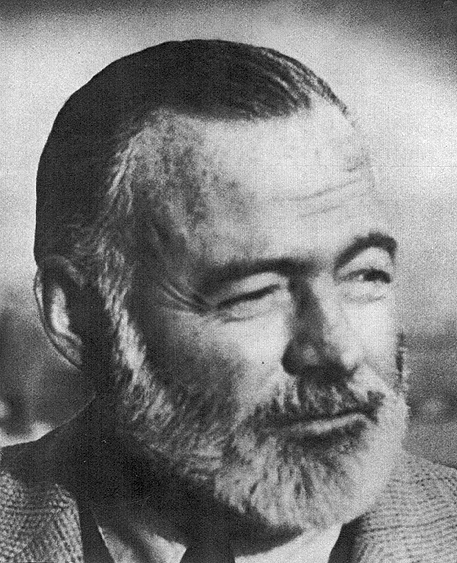

Hemingway to Dietrich

You are getting so beautiful they will have to make passport pictures of you 9 feet tall. What do you really want to do for a life work? Break everybody's heart for a dime? You could always break mine for a nickel and I'd bring the nickel. In a recently released letter dated June 19, 1950, at 4 a.m.

You are getting so beautiful they will have to make passport pictures of you 9 feet tall. What do you really want to do for a life work? Break everybody's heart for a dime? You could always break mine for a nickel and I'd bring the nickel. In a recently released letter dated June 19, 1950, at 4 a.m.

Tuesday, March 27, 2007

Withdrawal?

Haven't watched a movie in over a week. On the newsworthy scale, this falls between "Brad Garrett has a new TV series" and "nuclear war."

Haven't watched a movie in over a week. On the newsworthy scale, this falls between "Brad Garrett has a new TV series" and "nuclear war."Between the months of September and February, I average about three or four movies a week, a schedule which makes my waking hours indistinguishable from the fictional scenes and shots that replay in my head. Only when I sleep do I get that blessed black blank screen, the one on which "The End" has just faded. For the past year and a half, I've devoured movies in order to get the most out of my Netflix plan, but now I've downgraded from three-at-a-time to two-at-a-time. L'Avventura and King of Hearts have rested idly on my desk for seven days now. Haven't been to the theater since I saw The Painted Veil, like, a month ago. The weather's getting nice and reality -- despite the groping it requires to navigate it -- suddenly seems interesting.

So I'm disturbed by a thought that zipped in and out of my head today like an actor making an entrance onstage, realizing it's the wrong cue and stepping quickly back off:

Do I miss the movies?

Admission: I don't need movies to live. No one does, regardless of how they effuse about their unslakable passion. But I often need movies to help me think, or to re-orient my perspective on life, or to simply tranquilize doubts and worries. To capture a bit of the past. To connect with others without speaking. And so on. Do I just not need any of that now?

And am I okay with that?

Monday, March 26, 2007

Damn those Bravo marathons

But I've said it once and I'll say it again: Frances Conroy's performance in the series finale of Six Feet Under is one of the finest pieces of screen acting I've ever seen.

But I've said it once and I'll say it again: Frances Conroy's performance in the series finale of Six Feet Under is one of the finest pieces of screen acting I've ever seen.

Sunday, March 25, 2007

'Supermarket tabloids and celebrity gossip shows are ... a fundamental part of a much larger movement that involves apathy, greed and hierarchy'

The New York Times read my mind, as it sometimes does, although the story it ran today on Joseph Gordon-Levitt is a tad glib for my tastes. Still, it's good that this anomaly of filmdom is getting some inquisitive press about his career, which has blossomed into the most involving and pure of his acting generation. After Brick (amusing movie, tremendous performance) and Mysterious Skin (great movie, tremendous performance) can't wait for The Lookout this Friday. Also, my friend Jason alerted me to JG-L's personal Web site, which features a revealing little video confrontation with the paparazzi and the buds of a potential recording career.

The New York Times read my mind, as it sometimes does, although the story it ran today on Joseph Gordon-Levitt is a tad glib for my tastes. Still, it's good that this anomaly of filmdom is getting some inquisitive press about his career, which has blossomed into the most involving and pure of his acting generation. After Brick (amusing movie, tremendous performance) and Mysterious Skin (great movie, tremendous performance) can't wait for The Lookout this Friday. Also, my friend Jason alerted me to JG-L's personal Web site, which features a revealing little video confrontation with the paparazzi and the buds of a potential recording career.

Thursday, March 22, 2007

Passion and conservatives

Poster Boy, perhaps drawing inspiration from the irony of the Cheney family, is about a closeted gay man and his neo-conservative father, who happens to be the bulldog senior senator from North Carolina. The movie has the lopsidedness of a liberal tirade and reeks of the off-putting earnestness of amateur actors and filmmakers, but there are a few fleeting moments when it passionately and levelheadedly denounces the hypocrisies of our times. Take this speech by the son to a reporter:

Poster Boy, perhaps drawing inspiration from the irony of the Cheney family, is about a closeted gay man and his neo-conservative father, who happens to be the bulldog senior senator from North Carolina. The movie has the lopsidedness of a liberal tirade and reeks of the off-putting earnestness of amateur actors and filmmakers, but there are a few fleeting moments when it passionately and levelheadedly denounces the hypocrisies of our times. Take this speech by the son to a reporter:What am I part of, Jack? An issue? Don't you get it? Issues are what they use to divide us. Sexual orientation, race, gender -- all issues that don't actually pertain to anyone except those being cut out and thrown away by the issue. Does it really matter to some farmer in Kansas whether or not two men get married in Vermont? But see, they need us to choose sides. They create these issues for us to cling to, to grasp at. You know they separate us into these divisions: Black, White, Gay, Straight, Rich, Poor. Blame it Christian, Liberal, Democrat, Conservative. Split. Different. Opposed. How can a cause be just if it pits people against each other?

Tuesday, March 20, 2007

Monday, March 19, 2007

Romance and Cigarettes Watch: On DVD in May!

My dear friend Beedow alerted me to this news item. Seems the righteous-looking movie musical Romance & Cigarettes will finally be available to a mass American audience in May. Read my previous tirade here -- I mean, how could this not be released in theaters? The official word, per Fox News: It got lost in the shuffle when Sony bought MGM a couple years back. I don't buy it. Look at the pedigree in this movie. There's another, bigger reason. It must suck. But who cares? Release the damn thing in May, or else.

My dear friend Beedow alerted me to this news item. Seems the righteous-looking movie musical Romance & Cigarettes will finally be available to a mass American audience in May. Read my previous tirade here -- I mean, how could this not be released in theaters? The official word, per Fox News: It got lost in the shuffle when Sony bought MGM a couple years back. I don't buy it. Look at the pedigree in this movie. There's another, bigger reason. It must suck. But who cares? Release the damn thing in May, or else.

Sunday, March 18, 2007

B-sides: Just a Gigolo

I've been on a Marlene Dietrich kick lately, and this led me from 1930's The Blue Angel (her breakout) to 1979's Just a Gigolo, a Cabaret-esque post-World-War-I melodrama starring David Bowie as, well, a gigolo. Dietrich came out of a 15-year exile to shoot a single scene, collect her $250,000 check and fade away again. Even though Bowie disowned it after a ravaging by critics ("It was my 32 Elvis Presley movies rolled into one," he lamented in 1980), I really want to see it, if only for Dietrich's performance of the title song, the last scene (screen or otherwise) of her career. But the movie's not on Netflix (seems there is no Region 1 DVD). The VHS is on eBay, but I'm reluctant to plunk down $28 for it. Has anyone seen this movie?

I've been on a Marlene Dietrich kick lately, and this led me from 1930's The Blue Angel (her breakout) to 1979's Just a Gigolo, a Cabaret-esque post-World-War-I melodrama starring David Bowie as, well, a gigolo. Dietrich came out of a 15-year exile to shoot a single scene, collect her $250,000 check and fade away again. Even though Bowie disowned it after a ravaging by critics ("It was my 32 Elvis Presley movies rolled into one," he lamented in 1980), I really want to see it, if only for Dietrich's performance of the title song, the last scene (screen or otherwise) of her career. But the movie's not on Netflix (seems there is no Region 1 DVD). The VHS is on eBay, but I'm reluctant to plunk down $28 for it. Has anyone seen this movie?This is the first in a continuing series on B-sides, a well-known term from the music industry that I'm adapting for my own purposes. B-sides, in this case, are movies that have been forgotten, overlooked, relegated to second-banana or semi-cult status, or are generally way off the radar of popular culture. Upcoming: Man about Town (an intriguing Affleckian trifle that went straight to DVD last year) and Losin' It (in which Jackie Earle Haley and Tom Cruise go to Tijuana to lose their virginity).

Thursday, March 15, 2007

I like to watch

Everyone is the other, and no one is himself. The they, which supplies the answer to the who of everyday Da-sein, is the nobody to whom every Da-sein has always already surrendered itself, in its being-among-one- another. Martin Heidegger, 1927

Everyone is the other, and no one is himself. The they, which supplies the answer to the who of everyday Da-sein, is the nobody to whom every Da-sein has always already surrendered itself, in its being-among-one- another. Martin Heidegger, 1927

Saturday, March 10, 2007

1. United 93

Slate's Dana Stevens, who gave the only wholly negative review of United 93, wrote: "[Director Paul] Greengrass' exquisite delicacy and tact toward all sides — the surviving families, the baffled air-traffic controllers, even the hijackers themselves — began to smack of political pussyfooting. What is Greengrass actually trying to say about 9/11? ... Why was this film made, and why was it made now?" Manohla Dargis asked the same thing in The New York Times. She goes on: "I think we need something more from our film artists than another thrill ride and an emotional pummeling. 'United 93' inspires pity and terror, no doubt. But catharsis? I'm still waiting for that."

Slate's Dana Stevens, who gave the only wholly negative review of United 93, wrote: "[Director Paul] Greengrass' exquisite delicacy and tact toward all sides — the surviving families, the baffled air-traffic controllers, even the hijackers themselves — began to smack of political pussyfooting. What is Greengrass actually trying to say about 9/11? ... Why was this film made, and why was it made now?" Manohla Dargis asked the same thing in The New York Times. She goes on: "I think we need something more from our film artists than another thrill ride and an emotional pummeling. 'United 93' inspires pity and terror, no doubt. But catharsis? I'm still waiting for that."From Greengrass' audio commentary on the United 93 DVD: "We wanted to create a film that allowed an audience to walk through 9/11 at eye level — that that would give us some basis for evaluating this enormously important event. That's what drove us separately to come together and try to make this film. ... These events happened. They must have looked something like this. And they drive our world today. ... That's why when people say, 'Is it too soon?,' I say, 'It's high time.' It's high time we went back to the events of 9/11 and explored what happened, try to see what went on, what happened. Because it's the most important event in our lifetime. Everything that's happened stems from it. And unless we find the courage to look at it closely, how can we possibly find the answers?"

Movies can do two things. They can say something and/or they can transport us somewhere. United 93 does the latter. So I greet the aforementioned criticism with a furrowed brow. Surely a professional critic should recognize that movies need not take a pronounced political stance to be worth a damn. Greengrass, his editors and his exquisite cast grab hold of us and put us on that plane. As macabre as it sounds, this is a gift. Movies are our most sensate medium. We use them to experience worlds and lives beyond our own. I see value in having a filmmaker take me into the cabin of United Flight 93 — the setting of one of the most mysterious and dramatic moments in U.S. (and human) history — even if it is a creative construction that, although meticulous, is impossible to verify in full.

Manohla Dargis did not experience a catharsis. I'm not sure if I did either. But I'm also not sure if that's the point. This is a movie through which we can bear witness to sacrifice. In my original reaction, I agreed with the Passion of the Christ comparison. These movies exist for us to share in the agony and adrenaline of lionized figures. The passengers were quickly deemed "heroes." They failed to take control of the plane, but they succeeded in saving us unsuspecting earthbound targets. Heroic, yes. The movie does not name these characters, though (during the final half hour, one passenger calls a stewardess simply, "Stewardess." I'm sure there was no time or psychological space for introductions). These were people reacting to a threat, as animals would, and then binding together to assail that threat. There were no individuals. There are also no backstories. No cutaways to distraught family members on the ground. All the emotion is organic. Most affecting are the phone calls — factually documented and transcribed — that were made as people realized they needed to get their affairs in order. One woman calmly relays the combination of her safe deposit box to her daughter. Most express their love simplistically; it's shattering to see how careful the passengers were to not give their grounded relatives any dash of hope; they knew the situation was very bleak. There is value in having this dramatized. It happened. It's important.

Emotional content aside, United 93 is a stunning demonstration of craftsmanship at all levels: in a studio's courage to bankroll and produce it, in a director's utter control of the film's tone and texture, in a cast's willingness to commit themselves to an exceedingly austere type of characterization, in the editors' razor-sharp judgment, in a cinematographer's ability to make himself and his camera disappear from our view — leaving no cushion between us and what's happening. Technically speaking, it is all a remarkable achievement. I'm fascinated by how movies are made, and there are few stories of movie-making more unique and fascinating than this one.

The DVD of United 93 is impeccable and provides the full scope. There's a great feature on the actors meeting with the passengers' families. Greengrass proves in his commentary that this event consumed him to the point where he needed to make this movie. He wanted United 93 to be about the breakdown of systems, how one unimagined event throws a wrench into the machinations of the FAA, the military, the media and civilian life on the ground. The only system that worked on 9/11 was the one in the cabin of United 93, Greengrass says. The passengers were left to fend for themselves, since nothing was trickling down with clarity from the top. (Indeed, military commanders were not notified that United 93 had been hijacked until four minutes after it crashed.) "We can choose to ignore our world," Greengrass says in the commentary. "These people had to act. There was no choice. They had to live and die with the consequences." If this is not the ultimate premise for a movie -- and a strong call for active citizenship on our part -- I don't know what is.

It's also important to remember that half the film takes place on the ground. Greengrass captured the confusing flow of information and disbelief in 45-minute takes, trying to conjure up the reality of that day. Air traffic controllers and some military leaders play themselves. They relived and reproduced their bafflement and creeping, crippling horror. An exercise in masochism? Maybe. But it's also the necessary act of bearing witness. What Greengrass and FAA operations manager Ben Sliney and his staff are able to recreate is really something.

I'm no flag-waving patriot. United 93 is not hero worship, nor is it a twisted revenge movie through which we can assail our own psychological damage. It is told straight, without pause or reflection or ornamentation. It's through this straight-telling that we can come to our own conclusions and, perhaps, catharses. I look at the three movies atop my top 10, and I see a slight pattern. Bubble's construction fascinated me. Bobby's political message moved me. United 93 does a little of both.

Yes, political message. After watching the film twice on DVD I came to realize that, yes, in addition to transporting us, United 93 is saying something. But it's not trying to say something. It makes a point by simply being. The last shot resonates with clarity today, exactly five and a half years after 9/11. We are fighting for the controls of our world as it spins toward destruction. But, unlike the passengers of United 93, we still have time to pull out of it.

Friday, March 09, 2007

2. Bobby

The most compelling kinds of movies are those birthed by necessity or urgency. Emilio Estevez needed to make Bobby. So he did. The way he wanted to. Without compromise. He made it for himself, not an audience.

The most compelling kinds of movies are those birthed by necessity or urgency. Emilio Estevez needed to make Bobby. So he did. The way he wanted to. Without compromise. He made it for himself, not an audience.I'm still baffled by Bobby's tepid reception. Bobby is the kind of personal, go-for-broke filmmaking that is sorely lacking amidst the locust-wave of superhero franchises, middling animated movies, stomach-turning slasher flicks and pretentious and/or ill-conceived "independent" ventures by the "low-budget" arms of major studios. Bobby was a beacon this past year. It had a conscience. It took a stand and didn't waffle. It had a spine, for Pete's sake. And Peter Travers -- that whore of whores -- decried its "insipid ineptitude." Ineptitude? Coming from a major critic, that word choice is manifestly irresponsible, because "ineptitude" connotes an across-the-board inability to complete a task. And it is objective fact that Estevez achieved what he set out to do. That is not debatable. Whether you liked or hated that achievement is the essence of your opinion, and hence your movie review. My guess is Travers saw the name "Emilio Estevez" and wrote his review before seeing the movie. You can hate Bobby for its earnestness, its politics, its contrivances and affectations. But to simply call it "inept" is prejudice, not analysis.

But enough about idiot critics. Well hold on. One more thing: Critics called it a bloated movie reminiscent of disaster pictures like The Poseidon Adventure. They're right. Bobby is a disaster picture. It ties a bunch of ordinary people to one location at one moment in time, and profoundly changes their lives with one event. Its plot is as predictable as Titanic's, but both these movies prove that it's not always plot that counts. What matters is character and execution. Bobby has scores of jewel-like characters. And its execution, especially that of its final sequence, is the work of a great filmmaker who needed needed needed to exorcise some emotion from himself.

For a fuller and fresher reaction to Bobby, read my first post. I have not seen the movie since it came out in November, and I've since had many arguments over its merits. For my top 10, I wanted to revisit it on DVD but it's not coming out til April. Perhaps then I will watch it again with a shrewder, more cynical eye, and its flaws will be indefensible. But I cannot deny the raw experience I had in theaters. This movie transported me to 1968, but by virtue of its themes existed urgently in the here and now. It is a call to arms (not the military kind) that unfortunately went unheard in 2006.

Thursday, March 08, 2007

3. Bubble

A couple years ago, Steven Soderbergh sauntered into Parkersburg, West Virginia, picked three residents to be his actors and made a moody, fascinating movie that burrows deep into a woman's psyche without the heavy-duty tools of your normal psychological thriller. The woman is played by a middle-aged recently-retired manager of the local KFC. And she's great.

A couple years ago, Steven Soderbergh sauntered into Parkersburg, West Virginia, picked three residents to be his actors and made a moody, fascinating movie that burrows deep into a woman's psyche without the heavy-duty tools of your normal psychological thriller. The woman is played by a middle-aged recently-retired manager of the local KFC. And she's great.Yes, Bubble is a little experiment (some people -- missing the point of the excercise -- balked at it). Soderbergh worked intently with his three actors, using their real homes as sets, coaching them to deliver what he needed from a scene, then putting a camera on them and filming the improvisation. What resulted from this experiment was a tidy, fascinating story about how three co-workers interact inside and outside of a doll-making factory. The story seems to be spun on the fly, like real life, but there is also a surgical precision to Soderbergh's direction. Never do we sense that this is a runaway train. Soderbergh knew what was happening even as his actors didn't. It's God, and man. And here we have a little Eden of a movie.

Those who enjoy learning about characters through their rich, mundane activities (think Junebug) will love the patience and alertness of Bubble, which captures the small tragedies that ebb and flow through Parkersburg, a depressing place where dreams of escaping are quickly brushed aside. I'm making it sound too romantic, though; Bubble is not about drama. It is about trying to bottle reality and make it behave like fiction on celluloid. It's about stretching the medium -- making it populist and accessible, and fashioning art out of the regular and the unlikely.

I'll admit: I love this movie for how it was put together as much as I do for the end result. The DVD has a making-of featurette and audio commentary with Soderbergh and the three principles. Debbie Doebereiner, perhaps the most unlikely movie star ever, is a joy to watch and listen to. Here is a woman that retired after 25 years behind chicken fryers and stepped right into the magical world of movies. Bubble was a crash course in filmmaking and acting, and her joy and newfound knowledge is evident in the DVD extras. Soderbergh brought her into his world, showed her how things worked, used her naivete and innocence to create a character and produced something very special. Bubble is another significant step toward the utter democratization of filmmaking. It's one-of-a-kind.

4. The Departed

Okay, first of all, I screwed up the ranking of the top 10. So everything gets bumped down, and it now becomes a top 11.

Okay, first of all, I screwed up the ranking of the top 10. So everything gets bumped down, and it now becomes a top 11.Let me start and finish with a bit of blasphemy and say that I've never enjoyed a Martin Scorsese movie as much as The Departed. Credit Scorsese for emboldening -- not overpowering -- William Monahan's gorgeous screenplay and the actors for taking it and running like hell with it.

"I'm gonna go have a smoke right now. You want a smoke? You don't smoke, do ya, right? What are ya, one of those fitness freaks, huh? Go fuck yourself."

Wednesday, March 07, 2007

5. Casino Royale

A gamble pays off. Daniel Craig, an aesthetically unlikely Bond, gives one of the year's best performances -- defying death and charming the pants off women onscreen and us offscreen, putting some muscle and humanity back into the atrophied spy archetype, his success buoyed by a literate and coherent script. See how much everyone benefits when a movie is well-composed and thoughtful, when it is written to us and not down to us? Casino Royale boasts some kick-ass sequences and scenes (the opening one, the first chase, the train conversation, the poker game) but the point is this: They all add up. Things fall into place gracefully and I found myself emotionally stunned during the film's climactic scene. Thrilled throughout. Delivered at the end. Two and half (short) hours in exotic locales with exciting people. Who could ask for anything more?

A gamble pays off. Daniel Craig, an aesthetically unlikely Bond, gives one of the year's best performances -- defying death and charming the pants off women onscreen and us offscreen, putting some muscle and humanity back into the atrophied spy archetype, his success buoyed by a literate and coherent script. See how much everyone benefits when a movie is well-composed and thoughtful, when it is written to us and not down to us? Casino Royale boasts some kick-ass sequences and scenes (the opening one, the first chase, the train conversation, the poker game) but the point is this: They all add up. Things fall into place gracefully and I found myself emotionally stunned during the film's climactic scene. Thrilled throughout. Delivered at the end. Two and half (short) hours in exotic locales with exciting people. Who could ask for anything more?

Tuesday, March 06, 2007

6. Shortbus

Voyeurism is participation, says Shortbus. If there ever was a movie we could enter, it's this one. My first thoughts will suffice here.

Voyeurism is participation, says Shortbus. If there ever was a movie we could enter, it's this one. My first thoughts will suffice here.

Monday, March 05, 2007

7. The Descent

This movie grabbed me by the throat in its first five minutes and kept me pinned down for the duration, frightening the breath out of me and pumping my blood full of dread juice. The Descent is aerobic in its scariness. It's working feverishly on four scare levels (yes, four). The first is phobic: A group of friends go spelunking. They worm their way through tiny passages. I'm not particularly claustrophobic, but this movie ignites a compounding panic by setting almost all its action in tight spaces.

This movie grabbed me by the throat in its first five minutes and kept me pinned down for the duration, frightening the breath out of me and pumping my blood full of dread juice. The Descent is aerobic in its scariness. It's working feverishly on four scare levels (yes, four). The first is phobic: A group of friends go spelunking. They worm their way through tiny passages. I'm not particularly claustrophobic, but this movie ignites a compounding panic by setting almost all its action in tight spaces.The second is sociological, for lack of a better word: A series of events throws the group into discord, which layers more strain on an already tense situation. The third is predatorial: There's unexplained phenomena in the cave that start to add pressure to the dangerous situation in which the group finds itself. The fourth is mental and spiritual: This aspect reveals itself at the film's end, but has been building all along. It deepens the psychology of the film, and makes possible the devastating final sequence.

The film looks great -- the visuals are vivid and kinetic, the colors are dangerously beautiful. It's seductive-looking. The cave scenes were shot all on set, and it's a seamless and terrifying world. The cast, which obviously was put through hell during shooting, is perfect -- especially our lead protagonist, Shauna Macdonald, who combines beauty and brawn and grief better than Uma Thurman did in the Kill Bills.

I like a good scary movie, but when things tread toward the "horror" end of things, I get wary. A plot reliant on gore isn't appealing to me. It's disturbing that movies like Saw and Hostel do bully business at the box office. There is plenty of stylistic and nauseating gore in The Descent, but there is much more at work. I won't spoil the particulars. This is a movie to be experienced. It's an adrenaline rush. It will stick with you for a long time. The dread will linger.

Sunday, March 04, 2007

8. The Prestige

This is how mainstream movies should be: whip-smart, with matinee idols steering a crackling plot that both requires your intelligence and urges you to sit back and be overwhelmed. It's an ideal sensation, to be entertained and mentally stimulated. The Prestige --named for the final part of a magic trick -- does both, thanks to Chris Nolan (hasn't made a bad picture yet) and Hugh Jackman and Christian Bale (two actors whose personalities are night and day but whose charisma level is off the charts). They keep us entranced and distracted with the fireworks of their duel, but all the while they're setting up a great trick on the medium of film itself. When The Prestige reveals its prestige, we are duly awed.

This is how mainstream movies should be: whip-smart, with matinee idols steering a crackling plot that both requires your intelligence and urges you to sit back and be overwhelmed. It's an ideal sensation, to be entertained and mentally stimulated. The Prestige --named for the final part of a magic trick -- does both, thanks to Chris Nolan (hasn't made a bad picture yet) and Hugh Jackman and Christian Bale (two actors whose personalities are night and day but whose charisma level is off the charts). They keep us entranced and distracted with the fireworks of their duel, but all the while they're setting up a great trick on the medium of film itself. When The Prestige reveals its prestige, we are duly awed.

Saturday, March 03, 2007

9. Marie Antoinette

This is the movie The Queen tried to be: a portrait of the vagaries of royalty. Marie Antoinette -- without trying to be an academic dissertation (like The Queen was) -- ponders how a monarch can command so much respect and deference but be a completely ineffectual leader. I question my use of the word "ponders," though, because Sofia Coppola isn't a showy meditator. Her movies are tableaus. Their souls are quiet and thoughtful. She creates and presents a world as she sees it and then, like a passive deity, simply watches how it evolves and conducts itself.

This is the movie The Queen tried to be: a portrait of the vagaries of royalty. Marie Antoinette -- without trying to be an academic dissertation (like The Queen was) -- ponders how a monarch can command so much respect and deference but be a completely ineffectual leader. I question my use of the word "ponders," though, because Sofia Coppola isn't a showy meditator. Her movies are tableaus. Their souls are quiet and thoughtful. She creates and presents a world as she sees it and then, like a passive deity, simply watches how it evolves and conducts itself.Versailles, rigid with the sclerosis of tradition, receives their new dauphine, Marie Antoinette of Austria, who is young enough to rebel against the system but not wise enough to put that rebellion to good use. Thrust into her role as queen, Marie first spends her time adjusting to the bewildering treatment, then surrenders herself to being pampered and cocooned. Tradition morphs into decadence. Outside the gates of Versailles, her public begins to boil with discontent -- though we, like Marie, never see them. Do people really need a leader on a pedestal -- primped and preserved into a goddess on Earth, untouchable and therefore out of touch? The film seems to ask that question, but never pursues the answer.

Coppola's Versailles is very beautiful and very real, and Kirsten Dunst finds the right note for Marie: equal parts naïve and knowing, like a child playing dress-up with conviction. Dress-up eventually becomes her reality, which makes the end vibrate with a deeper tragedy. In the final scene, it's apparent that Marie believes she touched heaven during her reign. But it was at the expense of the people who are now dragging her from her Eden.

Friday, March 02, 2007

10. The Lives of Others

This beat Pan's Labyrinth for the foreign language film Oscar, and I suppose that's how it should be. The Lives of Others is exceedingly intimate for a film that spans a decade and concerns East Germany under the Stasi, which employed people to spy on their fellow citizens. The film's setup is kind of like Rear Window, but with audio instead of visuals. Ulrich Mühe, in a performance lacking all vanity and pretense, plays the man who listens to the lives of a playwright and his actress-muse (played by Sebastian Koch and the disarming Martina Gedeck, pictured). Like Jimmy Stewart, Mühe is propelled by certain events from observation to action, but to decidedly different results. This is a film about social and psychological invasions, and how a society collapsed in on itself because, for all its snooping and subterfuge, no one was really sure who was watching whom. Apart from this, it's also about small kindnesses selflessly executed, and about how the only lives we should be digging into are our own. The end -- when Mühe gets an unexpected look at his own unexamined life -- is the film's greatest pleasure.

This beat Pan's Labyrinth for the foreign language film Oscar, and I suppose that's how it should be. The Lives of Others is exceedingly intimate for a film that spans a decade and concerns East Germany under the Stasi, which employed people to spy on their fellow citizens. The film's setup is kind of like Rear Window, but with audio instead of visuals. Ulrich Mühe, in a performance lacking all vanity and pretense, plays the man who listens to the lives of a playwright and his actress-muse (played by Sebastian Koch and the disarming Martina Gedeck, pictured). Like Jimmy Stewart, Mühe is propelled by certain events from observation to action, but to decidedly different results. This is a film about social and psychological invasions, and how a society collapsed in on itself because, for all its snooping and subterfuge, no one was really sure who was watching whom. Apart from this, it's also about small kindnesses selflessly executed, and about how the only lives we should be digging into are our own. The end -- when Mühe gets an unexpected look at his own unexamined life -- is the film's greatest pleasure.

Thursday, March 01, 2007

11. The Proposition

The baddest badass in the Wild West would have a tough time with the lethal, contentious rogues who roam the Outback in The Proposition, John Hillcoat's violent fable of fraternal dischord in 19th century rural Australia. Ray Winstone, playing the lawman of a feral terroritory, says he'll spare outlaw Guy Pearce's life if he finds and kills his older outlaw brother (Danny Huston) in nine days. The production value of the movie is impeccable: the landscape is beautiful, but it is a dangerous beauty, and the actors are seamlessly dirtied up, both physically and psychologically. The only currency in this godforsaken land is revenge and threat and intimidation, and it's fascinating to watch Winstone reconcile his quest for justice with his desire for peace. Emily Watson plays his fragile wife, and the two create a strange, sad relationship that is withering in the harsh heat of lawlessness.

The baddest badass in the Wild West would have a tough time with the lethal, contentious rogues who roam the Outback in The Proposition, John Hillcoat's violent fable of fraternal dischord in 19th century rural Australia. Ray Winstone, playing the lawman of a feral terroritory, says he'll spare outlaw Guy Pearce's life if he finds and kills his older outlaw brother (Danny Huston) in nine days. The production value of the movie is impeccable: the landscape is beautiful, but it is a dangerous beauty, and the actors are seamlessly dirtied up, both physically and psychologically. The only currency in this godforsaken land is revenge and threat and intimidation, and it's fascinating to watch Winstone reconcile his quest for justice with his desire for peace. Emily Watson plays his fragile wife, and the two create a strange, sad relationship that is withering in the harsh heat of lawlessness.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)